Mark Lambertz: Organisational Design, Weak Signals and the Future

Context

Note

Mark Lambertz, is a renowned thinker in the fields of cybernetics and organizational design. He is the author of several essential books such as "Freedom and Responsibility for Intelligent Organizations", "The Intelligent Organization", "Better Decisions with Red Teaming", "Responsible Leadership in a Complex World" and "Leading by Weak Signals: Using Small Data to Master Complexity". He helps organizations such as Bosch, BNP Paribas and Metro AG improve their processes in the digital world.

Mark Lambertz, is a renowned thinker in the fields of cybernetics and organizational design. He is the author of several essential books such as "Freedom and Responsibility for Intelligent Organizations", "The Intelligent Organization", "Better Decisions with Red Teaming", "Responsible Leadership in a Complex World" and "Leading by Weak Signals: Using Small Data to Master Complexity". He helps organizations such as Bosch, BNP Paribas and Metro AG improve their processes in the digital world.

Interview

July, 2024

Boyan: Mark, how did you end up in this field? Also, please be patient with some of my questions, as my experience with cybernetics is limited.

Mark: I would like to challenge that! More people are acting according to cybernetic principles than they are aware of. We are often intuitive cyberneticians when we do things like risk assessments or plan how to gain more control in a situation. And control, of course, is not in oppressive terms but more in achieving a goal aligned with our interests.

But back to your question, how did I end up here talking to you? I was self-employed for 20 years, working at an agency I co-founded with my friends. Eventually, I decided to move on from that to pursue my real passion, everything related to organizations. I have always wanted to be something like a Renaissance man of organizations—to be able to work on anything from leadership processes to culture. This is the best way to understand how things work and what changes are necessary to improve organizations.

Boyan: Do you remember the first time you heard the term “cybernetics” or were exposed to related ideas?

Mark: In the late seventies, I encountered the term related to robotics and artificial intelligence in the science fiction context. However, my first conscious contact must have been much later, around 2012, when I tried to get a deeper, more holistic understanding of how things work and summarize my knowledge. I came to it from the agile and lean school, continuous improvement, Kaizen - you name it. All those tools that help us understand systems and how they adapt to changing conditions better. How do some systems not only survive but thrive as valuable objects?

I used to draw some of those ideas out, and someone must have told me, Mark, that this is system thinking. Then I met a very good friend, someone I call a “walking wiki” - a person full of knowledge - Ziggy Becker is his name. He accelerated my learning journey, and I dove into systems thinking, cybernetics, and everything related.

Boyan: Your path is interesting since you moved from practice to theory. I have seen this more the other way around, where people acquire knowledge in academia and then apply it in practice.

Mark: Yes! For me, it was completely the other way around. Around the age of 25, I had to make a new decision on my leadership style. At that time, the company was growing, and it became apparent that I couldn’t control everything; I had to learn to give up some control. I needed to adopt more decentralized decision-making. Much later, I discovered the formal framework I started applying - participative management. The basic principle is that the most knowledgeable person should have the highest decision power. And that would almost by definition not be me - one of the organization's bosses.

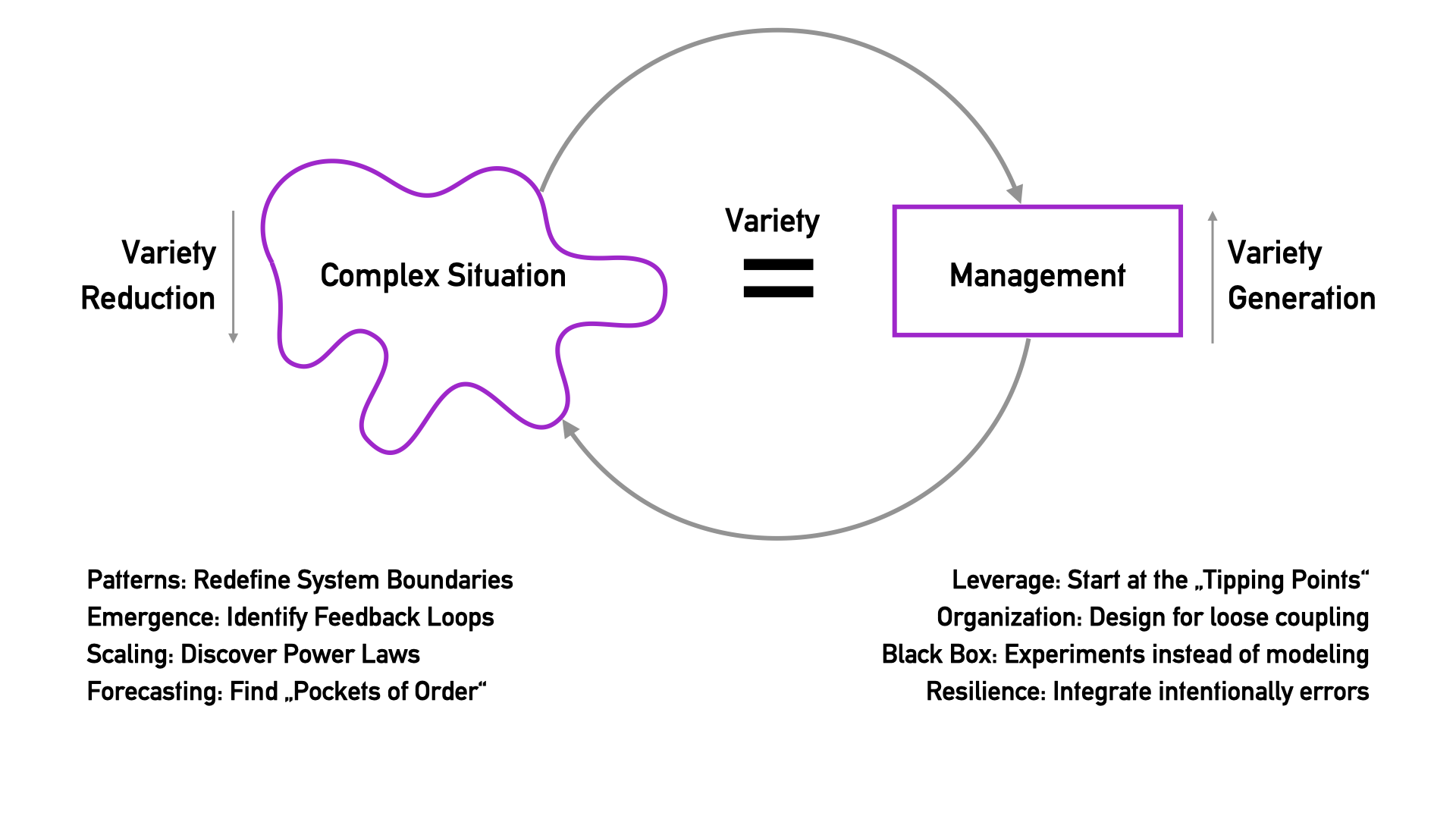

Boyan: This reminds me of Ashby’s Law of requisite variety. Do you think you started to do variety engineering back then, trying to match the complexity of the people “under” you?

Mark: Exactly. Later in life, I learned I was always “dancing” with variety; it was Ashby’s Law in action. I knew I couldn’t know everything, but I had people with systems states that were impossible to generate within myself; therefore, I decided it was their freedom to make the decisions. I hoped that they could behave as accountable as possible, but at the end of the day, I kept the responsibility. I absolved them of the stress of making a wrong decision, even if they were the expert taking those.

Boyan: In a way, you were dealing with black boxes. This reminds me of the theory that one person can hold the complete relevant information of the work of mostly six people, matching their variety. Was that when you started to think about measuring signals (I liked your Leading by Weak Signals work) and organizational design? How did you begin to set up hierarchies and other structures?

Mark: In the early days, there were a lot of experiments at the company. At the very start, it was just enough to be in the room. You could “feel” if things are working in a good atmosphere. But then the company grew to 20 or 30 people. At that point, I started doing my Gemba walk (the lean ritual), which is management by walking around. Mark Andreesen from Netscape used to do this in the old days. In this way, you could show your presence and allow people to share information. Following the erraro humanum est (“to err is human”) principle was fundamental in that context. Be solution-oriented; if someone makes a mistake, blame is unnecessary. This was built in our culture. Our job as managers was to create the conditions for our knowledge workers to be successful. Most of the time, it means just leaving them alone for their job.

Later, though, when we grew to more than 40 people, we discovered that we needed more structure and processes. For example, we had to rethink how we acquired customers and set invoices—even basic things like that. We also learned to be more efficient in other parts, such as not underestimating the complexity that different requested work packages can take. This was all difficult since it was just the early days of digital products. Remember, we founded the company in 1995.

Boyan: At that time, what was the knowledge transfer of such frameworks between the US and Europe? Where was the adoption stronger and earlier?

Mark: Of course, there was a lag between us and Silicon Valley, but it wasn’t as big as you would expect. Everybody was looking at them; for instance, extreme programming was all the hype back then. The interesting part was how the core principles of agility were already in the company even before we were conscious of it. For instance, from day one, we always had a task board and were doing dailies. During our breakfast, all eight to ten of us would talk about what was done yesterday, what was happening today, and if anyone needed support. Our number one bold rule, which turned out to be a mighty variety controller, was: it’s okay to make mistakes, but please talk about it. We didn’t want anyone to be a single hero who tried to rescue a project over a weekend on long nights fueled by coffee. We didn’t want to be surprised like that, since in those situations there’s no time to make a good decision if you don’t know you are in trouble. We wouldn’t blame anyone for underestimating complexity or overestimating one’s capabilities. But we would reward openness, which allowed us to solve everything.

Boyan: How did the theoretical knowledge of such frameworks spread between you and the other managers? At some point, you had a lot of experience, but how do you teach other people, especially the ones who participate in the daily rituals, the domain people, and the technical people?

Mark: In the beginning, this was a completely informal process. I think we were pre-selected somehow since we all had too high doses of endorphins in our blood. If you measured, I am sure you would conclude that we were curious and excited about anything new. It was super cool just to be able to learn new things that improved our work—even small things like learning keyboard shortcuts. We were in continuous positive competition, pushing together as a team to learn to be more efficient in our daily work.

Boyan: I wonder how much the environment in such companies influences the culture. You know of the Berlin's ART+COM and how that “hacking” and exciting culture permeated their work. How do you design the environment? For example, what do you think of Valve Software’s internal open marketplace of projects, where people apply to different projects themselves instead of a top-down management decision approach?

Mark: It depends. My position on this is full of ambiguity. On one side, it is crucial, but on another, a dog and pony show with a cool kicker in the corner and a food bar won’t automatically result in a great, humanistic culture. It can be abused.

Boyan: The difference is whether the culture has grown organically or was forced on the teams.

Mark: Yes. But ideas such as at Valve can absolutely work. There are many examples of companies with two managers and thousands of employees. At the moment, it is super interesting to see what Bill Anderson is doing as the CEO of Bayer, trying to fight the “bureaucratic monster” - in his own words. For me, it is simple - it is good to have the environment, but we need rules and structures, methodologies, and working frameworks that help us avoid reinventing the wheel. The human at the center of all of this remains the decisive factor. All questions of leadership are always about motivating people to perform instead of pushing them to do that.

Boyan: So, a focus on the incentive structures?

Mark: Yes, and just being a good role model. The same people with a different leader can achieve new things. There’s a funny saying from Karl Valentin, the German humanist from the 1920s: “We don’t need to educate our kids. They will imitate us anyhow.”

Boyan: For good or worse!

Mark: Yes. Setting the tone and standards, rewarding and sanctioning behavior—it all starts at the very top. And this is why I love the Viable System Model so much. The highest system, the highest authority—system 5—creates the identity, setting the norms of the organization—all norms—formal, informal, written, unwritten. And remember—the informal ones can be at least as powerful as the formal ones.

Boyan: These questions of leadership in complex environments make me think about a sports example. Some people say that modern football has become too tactical. We have managers such as Pep Guardiola, who, after initially perfecting the “tiki-taka” brand of possession and automatism, football at Barcelona has influenced countless other teams. He uses a ton of data analysis, and his work is more “mechanical” than “emotional”, one could argue. He has the financial opportunity to purchase the best players who can fit into his system. And then, on the other end of the spectrum, you have teams such as Real Madrid, with coaches such as Zinedine Zidane and Carlo Ancelotti who just want to motivate their players and give them creative freedom. Looking at match-ups and results, we can see them regularly coming on top in diverse scenarios being very adaptive. I feel there’s something cybernetic going on here.

Mark: Definitely. And that again comes to the main point - what is the human in the center doing? Should we give them a detailed plan - “micromanage” them, or is it better to set an inspiring, motivating goal? In the 1990 World Cup, Western Germany became champion, and one of Franz Beckenbauer's final words to his team before entering the pitch was - “Let’s go out and have some fun. Let’s play some football!” And that’s what perhaps propelled them to success. The question should not be what is better or worse but what works.

Boyan: It’s like the difference in that biblical story about giving fish or teaching one to fish. Now, let’s talk about efficiency and political structures. For example, some political systems that are more dictatorial can be more efficient, at least in the short term, because of their ability to make and enforce decisions on relatively short time scales. They can also mobilize resources at scale and speeds unimaginable to more “democratic” forms of government, such as in the EU, where all countries often have to reach a consensus for decisions before taking action. However, in the long term, there might be a Black Swan event that will destroy them. So, slower and perhaps more bureaucratic, distributed systems such as the school system in Germany (which is different in every German state) can be more effective in the long term since it has more states to match the environment. To quote Nassim Taleb, it is antifragile, more like a living thing adapting to the local environment.

Mark: Where do I start? First, as a general remark, everybody needs to accept the existence of complexity. It might sound trivial, but it is a problem I see often in larger organizations. We need to let go of the idea that in complex systems, we can find a solution to every problem. I frequently work with engineers, and they need help with this.

Boyan: Probably because the problems they deal with are more discrete and “deterministic”.

Mark: Exactly. And the hardest thing for me is to convince them to let go, that this is not a problem. Of course, we have to support the engineering mindset in many situations. After all, if those engineers are designing the break in my car, I hope they have looked at every problem and found a solution. I love perfection in that context. However, even with the most intelligent people in one room, issues are sometimes so complex that we must work differently. We must accept that we can’t know everything and that these strange interactions and intertwined things are happening. Delays make the system intransparent, and even if we discover the patterns, it remains often impossible to predict the behavior of a complex system. You can try with limited success, but eventually, the efforts will be futile when encountering a real “wicked” problem.

In such situations, I love the principle of subsidiarity, which gives the lowest operational units the highest decision power. These people understand that the customer—the central management function—needs to be closer to the problem.

Boyan: In a perfect world, we wouldn’t need managers. The workers should be self-organizing.

Mark: Maybe not managers, but you will always need the function of management. Suppose you take the VSM and look at its building blocks. In that case, you have the function of delivering value to an ecosystem - it doesn’t matter if it’s an ant colony or a global enterprise - there’s always some sort of value exchange - whether that’s energy, money, or whatever flowing and consuming resources. On the other hand, there’s always also the management function, which must relieve the operations from tasks that are not directly related to value generation - it is a service function, not related to value generation.

Of course, the maturity of the local units determines the strength required of a central management function. For example, there’s a big difference in making decisions for my 3-year-old and 16-year-old, who are much more autonomous. This influences the subsidiarity principle.

Boyan: Let’s talk a bit about signals. I remember Stafford Beer explaining how even the best intentions can lead to catastrophic decisions since there are many unseen delays in information flows. There is almost always a delay in getting information. What does that mean for the more bureaucratic systems we must design and manage, such as governments and large corporations? There are some extreme ideas, such as having digital tools that provide direct feedback to the government. For example, if I see trash on the street, I can instantly express my dissatisfaction with the local government. What are your thoughts on gathering signals and shortening feedback loops? How do we improve the issues that we face?

Mark: This is a classical pattern; every organization faces it. It mainly depends on the number of layers in the hierarchical structure. One deciding factor is the speed of information; the second is the almost inevitable decrease in quality or noise in the information itself (added willingly or unwillingly). In the VSM, every time information passes through a system boundary, it goes through a transduction process. For example, the CEO defines a target, but then the designers in the organization interpret it differently, and finally, it changes entirely by the time it reaches the engineers. Each of those groups speaks their language. We return here to the principle of subsidiarity. Instead of the people sitting in the central functions, in the “ivory tower”, who are busy with themselves, you push the decision to the people with the most suitable skills and empower them to take calculated risks because by the time signals reach you, it might be too late. You have to reward them for making decisions, like in organizations where teams are treated like micro-enterprises with their own P&Ls. If you do a good job, you get a bonus. It’s important to know here that I’m not talking about some Darwinist approach where the strongest survive, and it’s a race to the bottom. One approach is called a “skip-level meeting,” where you skip a level in the hierarchy. This is bound to offend some people, and middle managers get frustrated if they are sidestepped.

Boyan: At some point, Elon Musk was frustrated with Tesla's bureaucratic system, so he created some simple, similar heuristics.

Mark: Yes, I have worked with CEOs who had open-door policies. Again, you see the importance of leadership style and being more focused on management by objectives and OKRs. Give targets and resources and let people do their jobs.

Boyan: Let’s discuss more significant systems, such as the global economy. There, many decisions are outsourced to machines - algorithms. That can lead to regrettable cascading effects. We are also drowning in signals - arguably, there’s too much information, and we struggle to focus on the important ones. Looking at events in the world, you can see how seemingly small local events can cascade into global crises with unexpected consequences for all of us. Now, here’s my question, and it’s a philosophical one. Sometimes, we see the world, and it does seem very fragile. This is at least the viewpoint of most people if you ask them. Or at least they will all admit the world is too complex. Sometimes, I agree with that view; at others, I think the opposite - this complexity stabilizes the world. Many actors are playing the game, with associated bureaucracies and sub-elements interacting and absorbing variety, resulting in the opposite of variety - viability, having the properties of a living, adaptive, complex system. Suppose we take the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. It seemed like the world stopped, but it kept turning; the economic system did not collapse. It survived. In your opinion, is the human world fragile or viable?

Mark: This is a very, very tough question. We are growing exponentially, and it is difficult to imagine the next 500 years if we look at the previous ones. The Earth is resilient, but I am not sure about us. But I prefer to be optimistic and have hope and belief that human resilience is also enough, even if we are currently putting a strain on our planet. At any rate, we should focus on the long-term perspective, have a 500-year plan, and act now.

Boyan: Many situations can give us hope. Coming back to the COVID pandemic left a polarized impression on most people. Still, if you look at it from the current vantage point, most people, around 60% in Germany, decided to vaccinate, and many followed strict social distancing policies. So many of the human population took risks with new medicine and overrode their instincts to fight an invisible enemy for the common good. I felt that we could pull together individually and collectively and go through challenging situations.

Mark: There’s one excellent German book called “Im Grunde Gut,” which explains how people’s fundamental nature is good and that we are more cooperative than selfish. There’s a lot of research to support this view. And there’s this saying: What is the whole purpose of playing a game of life? It is not to win but to keep playing.

Boyan: That’s a very good metaphor. Let’s talk about books. One of my favorite ones is Jurassic Park. Most people are aware of the movie but haven’t read the book. When I read it as a kid, I was fascinated by the Dragon curve fractals depicted at the beginning of every more extensive chapter of the book. Those fractals showed the growing complexity of the system, starting with simple patterns and reaching staggering detail and scale. Even one of the main characters, Ian Malcolm, the mathematician, was evidence of how much Michael Chriton was inspired by systems thinking. There is a lot of dialogue in the book also about chaos theory. In the story, in the beginning, humans created this park, which was perfectly functioning. Still, all it took was for one person to disobey the rules for several minutes for the whole thing to cascade, resulting in catastrophe. I think there’s a lot of evidence of how an extensive, artificial system can be highly fragile because of its controlling nature. It also reminds me of how Asimov described the world of Trantor, where galactic human civilization seemed at its peak. At the same time, the seeds of its downfall were already present but invisible, with the eventual collapse impossible to avert.

Mark: Hopefully, we can better deal with our planetary feedback loops because the signals are already there. But Stafford once wrote a letter with an interesting saying: “We should never underestimate the power of ignorance as a variety attenuator”. People can justify everything through their own epistemological processes in the face of facts. This is why lasting change usually happens only through a crisis. Any smoker can attest to that; when their health becomes affected, they decide it’s time to change.

Boyan: Yes, and sometimes, if the crisis is not too big - big enough to end us all - it can act as a “vaccine” of sorts. For example, Brexit resulted in a more united European Union. At the same time, the crisis in Ukraine can remind our current European generation of the horrors of a potential world war that we have already forgotten. In the long term, such local shocks can improve our larger systems' viability, such as how exercise tears muscle cells, resulting in their growth and overall resilience.

To return to cybernetics, I think the field disappeared under this name. If I talk to most people in my life, they wouldn’t be aware of it and just associate it with science fiction. It became part of other fields, such as more quantitative complexity research. Do you think the field is coming back?

Mark: I think cybernetics has become normal, which is why you might feel it has disappeared from the public discourse. There was a competition about how we would name those fields before, whether they should be information theory, cybernetics, or informatics. We know how informatics eventually won. But there’s still excellent research on social theory and other fields, such as complex adaptive systems.

But to be honest, some of the early ideas of cybernetics have proven to be a bit naive. For example, that drawing from “Designing Freedom”, where Beer explained the odometer. In a modern world, that could be the perfect dictatorship tool, Orwell’s worst nightmare, with hazardous effects on our society. This is why cybernetics was sometimes automatically associated with mass control. But these are often silly arguments since any technology doesn’t have a moral associated with it - a knife can be used for cooking and murder. It is our responsibility and our intentions that decide morality.

Boyan: What is the difference between more quantitative and qualitative work? I have been working through very mathematical first-principles works, such as the works in the Santa Fe Institute and the original papers from Shannon, von Neumann, and the rest, thinking about entropy and the like. Then, I saw Beer’s work, which almost felt philosophical and political. And there is your work on power laws and weak signals. What do you think about this contrast?

Mark: To quote Bruce Cameron, “Not everything that can be measured counts, and not everything that counts can be measured.” We always need context on the data. We need to be hyper-aware of how it was collected —this is the sense-making process.

Boyan: For example, GDP is very measurable, but its usefulness depends greatly on the context.

Mark: It is essential to connect data points to some goal setting. I like the OKR stuff because there’s a way to connect a qualitative measure with a quantitative key result. For example, I want to be healthy, but how can I make this goal more tangible? I can connect it to measurable things, such as how much water I should drink or how many times I should go to the gym. So, I can use quantitative indicators to see how far I am to achieving a qualitative goal. This is a beautiful method of absorbing variety. You can go from high-level strategic goals to actionable, measurable ones.

Boyan: Part of my work is advocating for a more motivating, inspiring vision of the future, one that the previous generations had in terms of science fiction and the like. We need more positive incentives. What do you think about that?

Mark: Yes, and for that - partially, at least - I blame Hollywood. They tell us stories of dystopia and destruction. We need to use our imagination to see the future, not in a cheesy way, but an authentic one. Despite all the horrible signals we get about climate, wars, and others, we need more positive visions. We need something attractive. Like Buckminster Fuller once said: “Don’t fight the old model; build a new model which is more attractive”.

Boyan: An issue is that we are still evolutionary pretty much the same as we were tens of thousands of years ago, and the algorithmic nature of the technologies that influence our culture are cashing in on the reptilian brain in us, the direction of our attention to more negative topics. Thank you. We could talk for many more hours, but we covered many important topics. Thank you!

Mark: Thank you!