Ghosts of Futures Past: Generational hauntology impeding progress

Author: Boyan Angelov

“To haunt does not mean to be present, and it is necessary to introduce haunting into the very construction of a concept. Of every concept, beginning with the concepts of being and time. That is what we would be calling here a hauntology. Specters are not part of ontology.” - Jacques Derrida.

The High Frontier

It is a hot July afternoon on the east coast of the US. The year is 1969, and this day will go down as one of, if not the most, important in human civilization’s history—a human is set to walk on the Moon. By sunset, we, as a collective human species, will break through the invisible border between our home and the rest of the universe.

Imagine you are a child witnessing this event. As you hear the clamor as the adults settle down in the living room in front of the TV, you stop playing in the garden and join them. First, you are confused. Why is everybody so silent all of a sudden? And there they are - the black-and-white pictures from the surface. It takes a second for you to realize what you see. The spectacular contrast between the bright moon dust, the starless darkness of space above, and the radio transmission's strange echo will be forever etched in your mind. The video transmission quality is low, but your imagination fills in the blanks. The nation holds its breath, and one person takes that small step.

For everybody who witnessed it, this was a watershed moment. They felt as if this was the first day of the rest of their lives - that nothing would ever be the same again. Within their minds, the realm of the possible expanded into science fiction. As a result, contemporary American culture extrapolated this decade of technological progress into the distant future, painting visions of flying cars, underwater cities, and robots.

Six decades in the future, we are barely starting to re-thread the same path. In P. Thiel's words, we expected flying cars but got 140 characters. This is an unfair comparison because if we look back at history, it is easy to realize that this quantum jump resulted from a global arms race rather than a purely altruistic endeavor to advance human civilization. Still, the memory of black-and-white static and echoed words was enough to inspire a generation of scientists and give everyone else a vision of a new future. That, however, was not my generation.

Problematics

"If a tree falls in a forest, and there’s nobody to hear it, does it make a sound?" -Popular thought experiment

As I grew older, I became curious how the eastern block reacted to this news. Fortunately, I could ask someone who lived through it directly. My parents were born at the same time as this golden American generation, but on the other side of the world, under the Iron Curtain. News of this momentous event did reach them, but much slower since the government propaganda needed time to decide how to show this story to the masses. Not everybody even had a TV at that time, and my father told me stories of how the whole neighborhood gathered in the living room of that one family that had one. They continued to live their lives as before - for them, nothing changed. So, what is the problem with this lack of a future vision?

When you hear the word - future - what do you imagine? If you had been there to ask the question, it would not have mattered if you had asked an American or soviet teenager. You would get a similar answer (even from the latter since they had a different, but similar in effect vision - that of soviet futurism) - the future is bright for all of us, and space is the next target. Fast forward 70 years into the future, what would a young person say today? The answer would be very different. You will get a dystopian answer, or at best - an uninspired one, with no concrete vision of the future. The year 2075 brings AI taking over, viruses, nuclear war, and climate catastrophe.

Lost futures throughout history

Human civilization's rapid technological and social progress can be deemed “unnatural”, at least for our psyche, which remains pretty much the same as thousands of years ago in hunter-gatherer societies. Thirty generations ago, in the early Middle Ages, very few things - if any - would change the lives of everyday feudal subjects. There would be no reason for the parents of a child in Bohemia, the year 1153, to expect a different life for their descendants. They would still get up before sunrise to start working the fields, go to church on Sunday, and occasionally go to war with a neighboring province.

That was about to change in the 19th century, so much so that change became the only constant. Relatively significant changes were readily observable by a single individual in one generation. The 21st century is ushering in even more changes within a single person’s lifespan (whose increase is another contributing factor). Nowadays, people can expect at least one major revolution, such as the internet, when they are alive. Humans have grown accustomed to extrapolating the rate of change into the future and currently in an exponential direction. It doesn’t matter if it’s a negative or a positive one, from the point of view of progress.

In the early 20th century, the first signs of social progress made people feel optimistic about the future, perhaps for the first time. Henry Ford introduced a 40-hour workweek for his employees, and worker unions expanded since the Royal Commission of Trade Unions recognized them in 1867. The Golden Twenties in Berlin made people forget the horrors of the First World War (but there would not be forgetting what was already brewing in the city streets). The WWII disaster dents the idea that technological progress alone is enough for the prosperity of our species and can be the very thing endangering its existence. It revealed that the extrapolation to a positive future in the work of Jules Verne and others could disappear overnight by a colossal reversal to the more basic instincts of our nature in the form of a global conflict. These examples marked junctions in history where a rapid positive change in the future was expected at scale.

Unfortunately, due to the wars in the middle of the 20th century, Fukuyama’s End of History coincided with the death of the future. It’s also easy to observe in our culture today. The constant film, music, and literature rehashes from more successful areas abound. For example, 80s music, 90s computer technology, and art are again popular in the 2020s in vaporwave, retrofuturism, and cyberpunk. Of course, cultural cycles have been a staple of our condition for centuries, but we are running out of options to revert to. There’s simply nothing to replace the rehashed work. We are nostalgic for a future that didn’t come to pass. How much is this a problem when extrapolated to a collective scale - that of a global, connected civilization? This is true hauntology: the ghosts of futures past, whether extrapolated at a historical junction or simply non-existent - influencing the present, closing its eyes to the possibilities of actual progress.

The current generation's lack of a productive, positive world mental direction is a self-fulfilling prophecy. It contrasts with the '60s and '70s generation in the US and the Iron Curtain, who had (admittedly) propaganda-inspired but optimistic, concrete views on human civilization’s future.

My life in three generations

Often, we can only consciously realize the peculiarities of our life history and views only when contrasting with those of another. This occurred when I met my wife and started sharing stories from my childhood with her. I told her I spent summers gathering Colorado beetles on a field in eastern Ukraine and reading old copies of Pushkin and Tolstoy. As someone who grew up in Western Germany, this reminded her of stories she used to hear from her grandmother - a person almost three times my age, two generations away. That was the first time I felt out of step with the Western timeline, but it would certainly not be the last.

Because of these conversations, I started observing my past through a changed lens. I remembered that I encountered this peculiar cognitive dissonance as a child already. I spent most of my childhood in Sofia, Bulgaria, but every summer, my sister and mother would visit my Russo-Ukrainian family in Mariupol, on the Azov coast. These three summer months (also every year until I moved to Germany for my studies) would leave an indelible mark on my life history.

We traveled to Ukraine by train. It was the same train my father had taken decades earlier for the first time when moving to Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, to study mechanical engineering, where he would eventually meet my mother. The journey took almost three full days as we traversed northern Bulgaria, crossed the Danube, then the planes of mainland Romania, and into the fresh, damp woodlands of western Ukraine before finally arriving in Kyiv for the last leg of our journey. In the capital, we would switch to a proper soviet train called “Platzkart” for our final trip to Mariupol. On day four, we would be greeted by the sound of seagulls and the stickiness of the humid air on the coast next to the train station. On the border between Ukraine and Romania, I remember the whole train being lifted several meters off the ground to replace the wheels. Because of the Second World War, when Romania was on the side of the Axis, there was an established difference in width between tracks there and in Stalin’s USSR.

Those days of train travel served as a buffer in my imagination because the way we would spend the summer in Ukraine would be that of another generation before me. I remember the old house that my grandparents built themselves in the 50s. There was no technology whatsoever in the whole house. A TV set with knobs and wheels, with a curved display, was at least three decades old, and it was surprising it was even in color. We turned it on only to watch Latin American soap operas and Jacques Cousteau on the weekends. I remember the World Cup 1998, which transported me to another world altogether. I remember my grandmother sitting next to an ancient radio on a tall chair, trying to get the finicky device to catch radio waves from Moscow at the appointed hour. She was a communist through and through, and she told me stories of the great Soviet Union and how she still votes for KPRF. There was not much to do in the summer other than go to the beach, right next to a “Pioneers Camp” - yet another thing that convinced me that I lived in the USSR. The tram we took to get to the beach in Mariupol was just a repainted version of a model that was used in the '60s already:

Other than that, I spent the summer perusing the literature at home. Stashed between various propaganda and Marxist literature were the journals “Наука и Жизнь” (Science and Life), which introduced me to soviet futurism. I imagined we would build a bright socialist future where the whole planet is united and we spread into computer space. This contrasted strangely with the few books that I managed to bring with me on the train - Jurassic Park, Tom Sawyer, Lord of the Rings, Treasure Island, and ALF (the latter was another curiosity to my wife since it was popular as a show much before than that in Germany - meaning that even in Bulgaria I was still on a culturally, and mentally different timeline than those in the West).

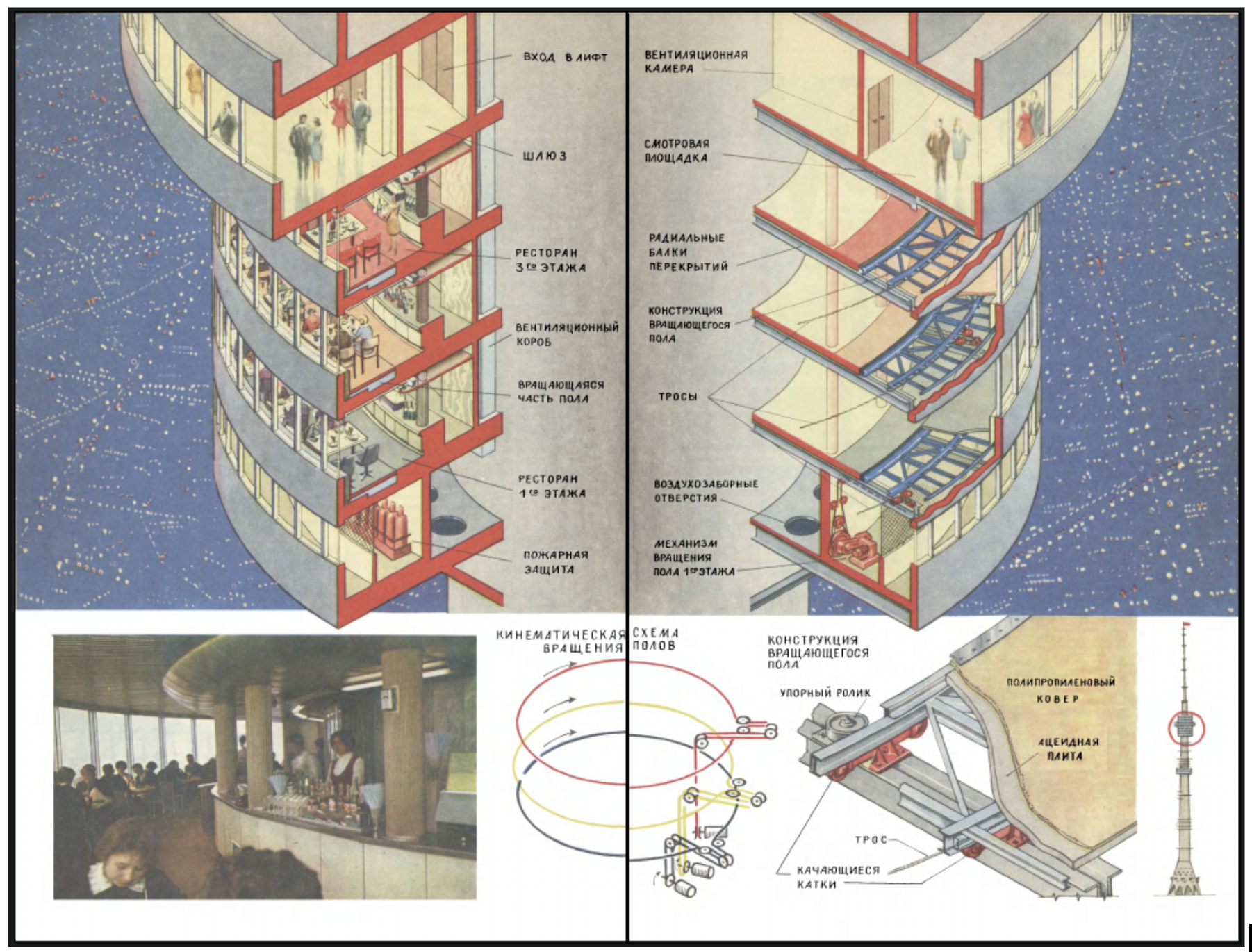

Here’s just a sample of what inspired me:

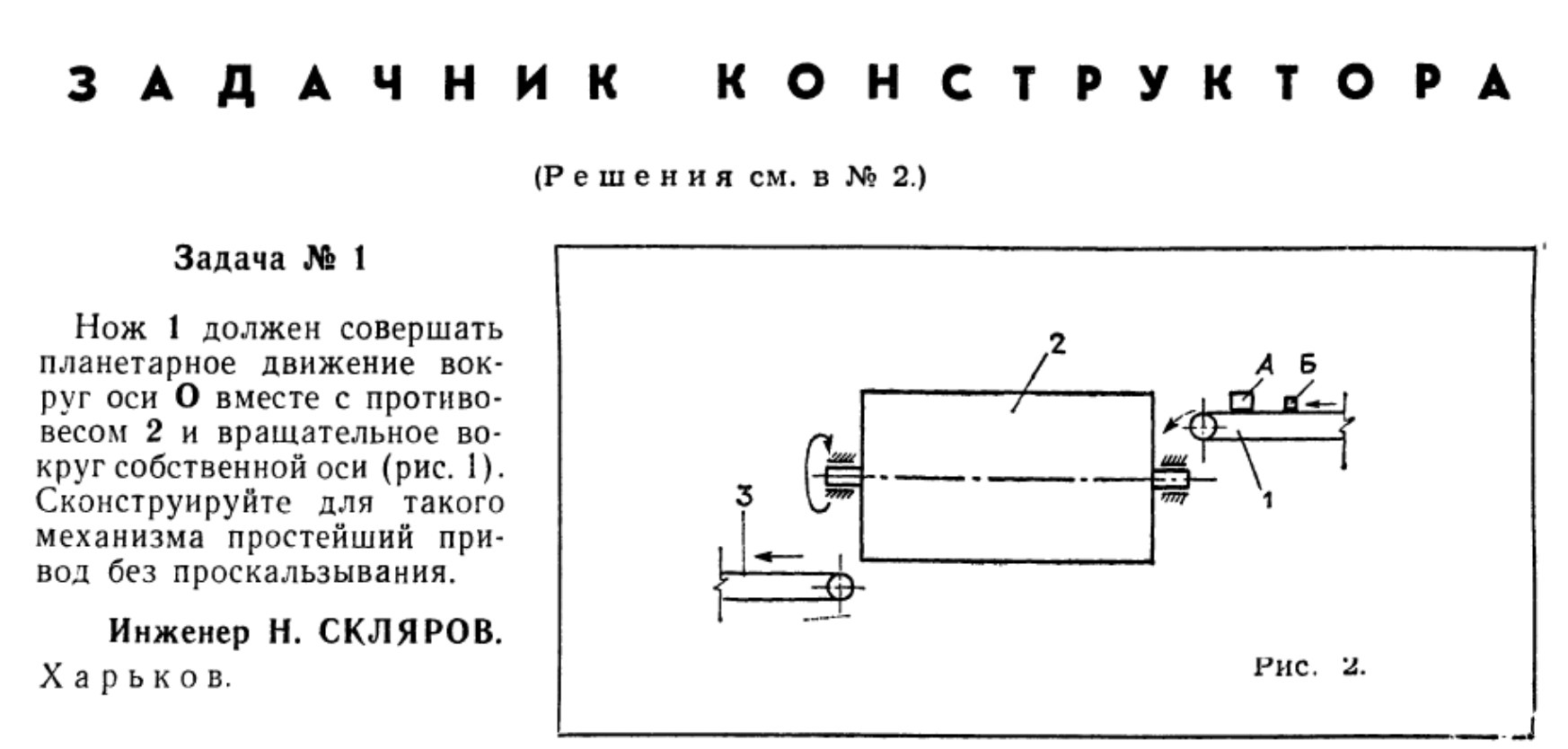

This is a vision of a rotating restaurant in a massive tower. There were other similar diagrams depicting cities in space or underwater. These magazines were not only full of utopian diagrams but reasonably practical things, such as this exercise for a young engineer:

Reading was the most fun we had, because we also worked the fields. The view of Azovstal next to one of our fields, the largest steelworks in the Soviet Union, the size of a small city, made me further believe in the wonders of communism:

Only much later did I discover that the lack of technology in my grandparents' place was a choice. I only had to walk twenty meters to the neighbor's house to play computer games. But I didn’t know this then, so it didn’t exist. It was a magical place, stuck in between history. And I inherited the same dreams of a space-fueled future that my parents' generation had. Different from Apollo, but ambitious nonetheless.

This vision of the future started fading away once I “synced” to the Western timeline when I moved to Germany for my studies. From then on, I began to inherit the prevalent dystopian, futureless vision, with only significant effort in remembering a different timeline to keep it at bay.

Outlook

The mental vision of the future, whether created by circumstance, culture, or conscious design, can be a powerful entity that can impact the present. When this occurs at scale, across a whole population, or even a generation, as in the case of the Apollo Programme, it can turn the tide of history and make a positive or a negative direction almost inevitable.

Our culture and state of progress indicate that in vast parts of the new generation of the Western world, there is a lost future. If we are ever to reverse the problem, we need to build a new vision, one that is more focused on solutions and visualizes achievable progress, which is empowering and motivating rather than dulling, causing anxiety and consumerism, where we can only retreat in the philosophy of nihilism, or the best case - absurdism. Otherwise, we risk haunting our minds, becoming stuck at the very end of history, just as the window of opportunity for a limitless future opened in July of 1969, remaining our crowning achievement as a civilization and a species.

Bibliography

- Fisher, Mark. Ghosts of my life: Writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures. John Hunt Publishing, 2014.

- Derrida, Jacques. Specters of Marx: The state of the debt, the work of mourning, and the new international. Routledge, 2012.

- O'Neill, Gerard K., and David Gump. The high frontier: Human colonies in space. Vol. 57. Burlington, Ontario: Apogee Books, 2000.

- Augé, Marc. Non-places: An introduction to supermodernity. Verso Books, 2020.