Raul Espejo: Complexity, Fragility and Chile's Project Cybersyn

Context

Note

Raul Espejo, an internationally recognized expert in organizational cybernetics, has significantly impacted the field through his research and writings. Co-authoring the book “Organizational Systems: Managing Complexity with the Viable System Model” alongside Alfonso Reyes, he explores the application of cybernetic principles to enhance organizational effectiveness. As the President of the World Organisation of Systems and Cybernetics (WOSC), he bridges theory and practice, emphasizing the relevance of the Viable System Model (VSM). Beyond academia, Espejo’s entrepreneurial endeavors and mentorship leave a lasting legacy, encouraging systemic thinking and innovative approaches to organizational challenges.

Raul Espejo, an internationally recognized expert in organizational cybernetics, has significantly impacted the field through his research and writings. Co-authoring the book “Organizational Systems: Managing Complexity with the Viable System Model” alongside Alfonso Reyes, he explores the application of cybernetic principles to enhance organizational effectiveness. As the President of the World Organisation of Systems and Cybernetics (WOSC), he bridges theory and practice, emphasizing the relevance of the Viable System Model (VSM). Beyond academia, Espejo’s entrepreneurial endeavors and mentorship leave a lasting legacy, encouraging systemic thinking and innovative approaches to organizational challenges.

He worked on Project Cybersyn, a Chilean initiative undertaken during the presidency of Salvador Allende, as an Operational Director. Cybersyn aimed to construct a distributed decision support system for managing the national economy. Designed as an electronic “nervous system,” it connected hundreds of firms to the government, allowing for swift decision-making. The Operations Room (Opsroom), adhering to Gestalt principles, provided a simple yet comprehensive platform for users to absorb economic information. Despite its historical context, Cybersyn’s legacy underscores the importance of systemic thinking and innovative approaches to organizational challenges.

Interview

April, 2024

Boyan Angelov: Let’s start with your most recent paper on the Westphalian Dilemma. Can you describe the main idea?

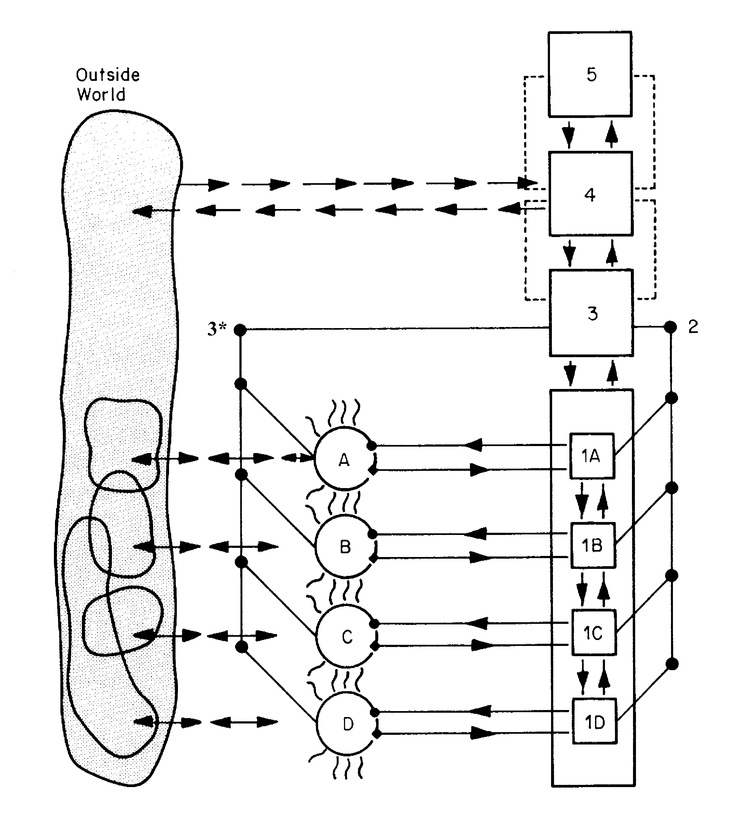

Raul Espejo: The idea is that national, international, global, and local levels must be properly managed. The problem is that often, you find hierarchical structures rather than distributed ones. The paper helps us see the fundamental idea of structural recursion - a central aspect of the Viable System Model1. In it, you have mechanisms for policy-making and mechanisms for policy implementation. These are the three fundamental aspects: policies, regulation, and implementation. The problem arises when the three are not linked, and the policies are not connected to whatever happens. Regulation is required to support the connections between the different parts of the organization. So, the VSM promotes understanding these mechanisms for policy creation and implementation. So that's where you can see that the mechanisms are inadequate when things are not well connected—understanding how the apparent aspects of policymaking, regulation, and implementation work together is essential.

Boyan Angelov: In the paper, you also discuss how different countries can collaborate more effectively on topics of shared interest. This made me think about the incentivization strategies for such collections of individual agents and game theory. Such settings must be significant for current issues, such as climate change or collaboration between different member states within the European Union. These insights help us balance the EU's individual and collective goals.

Raul Espejo: The critical issue is that if the mechanisms that relate the local parts to the global parts are inadequate, you may have situations where the local interests could be better related to the global ones. So, the issue is that the local problems lead to some degree of autonomous behavior. Because there is too much variety in the local aspects, the organizational resources must respond to more variety2 than usual. At that stage, the global may find that it cannot succeed in connecting to the local because the latter is making decisions on its own and is behaving autonomously. The global is losing control of the situation. It starts behaving autonomously and is losing control of the problem, becoming more detached from the local. The outcome is that it starts to ask for more and more control - more connections with the local, destroying the autonomy of its parts.

So if global management increases its demands on the local, when it needs more capacity to respond to its environment, it finds that how it relates to the global is reducing this capacity. So, precisely at the same time that the local needs more autonomy and flexibility, the global is restricting its behavior, and that's where you start to see the conflict between the global and the local. So, at that point, the global level is reducing flexibility while the local level needs more.

Boyan Angelov: You also researched the cybernetics surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. In that case, we could observe how collections of autonomous local governments needed to collaborate and coordinate their responses. They had to be flexible but also exercise significant control over their citizens. Do you have some lessons we can learn from this situation, some cybernetic lessons about the future, and how we can better deal with such problems?

Raul Espejo: The most important thing we need is more flexibility. To respond to situations like the pandemic, you must amplify local management and attenuate this local complexity. So that's what we connected to the ideas of amplification and attenuation, and that's where we see how you can design what we call variety engineering, how to engineer the variety of the situation so that you reduce the complexity of the problem. Still, simultaneously, you increase the variety of management options.

If that doesn't happen, the variety of management doesn't grow, and the variety of situations needs to be appropriately restricted. Then, you start to have situations out of control that need to be more restricted and precisely managed. And where you have what I have just mentioned, variety engineering, you need to build up more precise forms of variety management to amplify the variety of management and reduce that of the situation - the environment. You have these different levels of variety amplification that need to balance the situation and lead to better performance.

Boyan Angelov: So to paraphrase your answer, in complex situations we need to reduce the complexity of the environment and at the same time increase the variety of the managers. How important are feedback loops and their length in this context? During the pandemic technology and data collection played a pivotal role, for example in monitor incidence rates around the world. How important was that for managing the impacts?

Raul Espejo: It is clear that increasing the understanding of the environment is very important if you want to restrict its variety without destroying flexibility and the interactions between different parts. You constrain its capacity to deal with the situation without limiting its capacity to manage the policy issues at hand. So, the point I'm making here is that the way to restrict the variety of the environment is by finding constraints. If you don't find constraints, the management of the environment becomes chaotic. There are too many things unrelated and unconnected. And that makes it very difficult to manage the complexity. On the other hand, if you work out the constraints, you are saying these parts are more significant and need to be in touch with these other parts. It is essential to reduce the variety of the environment, maintaining the most significant connectivity among the parts of the environment so that the organization can focus its attention on those aspects that are the most significant and handle them properly.

Only very occasionally - by exception - do you find that certain things go out of the regulation of the environment, and they need to be paid attention to at the global level. So that's where I think finding fundamental constraints in the environment creates more appropriate structures. What you did as you found constraints matches these constraints with organizational and structural capacity. With that, you increase the chances of these autonomous relations. As you do that, you must remember that these environmental constraints will somehow generate unexpected performances or behaviors. And still, you need to have the capacity to manage that. That is not going to happen at this level. The organizational structure of the autonomous units will need the intervention of a more global system. And that's where you have the more global system connecting by exception—it's not the most desirable thing, but by exception. You have it involved in managing aspects of the environment, which most of the time should be in the hands of the local strategies.

Boyan Angelov: What is the role of information and data in all of this? In the modern world, it's easy for managers to get performance data from the environment. For example, if you're a manager of a software organization, you have hundreds of people working below. And because they use digital tools, you can always track their activities and performance. You get a ton of information about what's going on. I guess this is a good problem for a manager to have. Do you think we have too much information about the environment? Is this a real problem nowadays?

Raul Espejo: Of course, it is a huge problem, and that's precisely what I was saying before the need to recognize constraints in the environment because if you don't find these constraints, what is going to happen is that there will be a massive amount of data forming the perspective off the organization. You need to have the possibility to constrain the environment and, in that sense, deal with the most fundamental data to increase the organization's performance, and at the same time, you open the space for more developments in the policy itself.

Boyan Angelov: Now, let’s talk about the Project Cybersyn. What would you do differently if you could participate in such a project now? We have much better technology available, as compared to 1971-73. Do you think there’s a place for such a project nowadays?

Raul Espejo: I would like to send this question back to you. Do you think there’s a space for Cybersyn-like activities in today’s world?

Boyan Angelov: I have a slightly negative view of centralized systems that collect data. I think about how much information our governments collect about us. If I remember correctly, Allende’s government invoked a similar sentiment back then. Information gathering is a key prerequisite for exercising control, and you can see it in autocratic governments worldwide. I think it can be a dangerous path.

We also have so much data that we outsource much of the decision-making to machines. Part of me knows that it is a good idea since algorithms are capable of fast predictions on topics such as the economy, but at the same time, this perhaps leads to further fragility in that system. We have the technology to compute and the information, but I am worried about having the control delegated to a machine or a non-democratic government.

Raul Espejo: So, if I understand what you're saying, it would be possible to manage large amounts of big data in democratic societies but not in those that are not.

Boyan Angelov: Yes, correct.

Raul Espejo: Right. That is significant because big data needs to be contained and managed following the principles of variety engineering: reducing the autonomous extrapolation of things without connecting with policymaking. It is important from my perspective, and I expect to see a good deal of understanding and recognition of meaning and purpose in situations. Now, if that is well understood, people shouldn’t assign meaning without the participation of the people. So, the chances are this will be autocratic and hierarchical and, therefore, not very valuable in the long run.

On the other hand, if we can reduce or have shared meanings and purposes, then we can start working out more the fundamental structures that will be able to handle the large variety of the big data that they just started asking about. What I would say to you is that big data management today is as significant and relevant as ever. So we have always had this difficulty of huge data and not having adequate capacity to restrict it and manage it without losing the overall purpose that we are interested in.

So, in a way, the answer to your question, in my perspective, is that we need to understand better how to generate purposes that are shared by the people affected by the policies that we are interested in. It is through that sharing that you get to find out and move in the direction of increasing the response capacity. So yes, today, it is as vital as it ever was to have a sense of things similar to the ones that we did in Chile in those years. The variety of engineering and structural design. All these things are fundamental. The only significant thing today is that at the same time, we have an increase in data; we also have the possibility, but not what people experience all the time. The chances for coordination of the activities of the parts. So if the parties fail to coordinate their responses, all these connections between shared purposes and implementation will not happen because people will simply behave in a very chaotic fashion. So today, I believe we need to increase our capacity to coordinate our activities at multiple levels due to coordination but not imposition. That's not the point. The point is coordinating. To respond better to the large complexity of the situation. And that's where I feel today is very significant in furthering our developments towards what was intended with the Cybersyn project.

Boyan Angelov: How careful should we be about taking lessons from historical projects? How easy is it to transplant learnings from one context to another? You talked about shared purposes, but do they really make sense worldwide? For example, Chile has a unique geography and history, both economic and political. How confident can we be about taking lessons from one place and using them in another? Or do you think there are fundamental principles about variety and complexity everywhere?

Raul Espejo: Well, if we extend everything we have been talking about, it is clear that every place, from the very local and detailed to the very general, can generate its own purposes for meaning. And work out local responses to the situations they are dealing with. So, there is no need for the same purposes everywhere. That is what we must avoid: thinking that what has been recognized as the key interest and concern here at one stage will be required everywhere. No, clearly not.

The important point in the end is to connect the parts. The views, values, and understandings we have here may be of value or interest to others, and that's where I think the ability to share views, meanings, and purposes is quite significant. But not as necessary to make them all the same is simply to have fundamental values and general ethical aspects that can be somehow understood everywhere and create the chances for their own management of complexity. So, there is no need to have the same management. The same is true regarding content - it is not necessarily the same everywhere.

Boyan Angelov: What is the relationship between complexity and fragility in a system? My intuition tells me that a more complex system is somehow also more fragile. On the other hand, a more complex system has more variety, thus increasing the capacity for change. Based on recent events worldwide, do you think a more complex world is also more fragile?

Raul Espejo: I would like to hear your own thoughts about it.

Boyan Angelov: To be honest, I swing between the two extremes. Sometimes, the world seems very fragile, for example, what happened in Israel, how a local terror attack cascaded into a wider conflict, similar to other situations. In another way, if we look at the COVID-19 pandemic, the whole world stays at home. Everything stopped, yet the economy chugged along, and now the whole episode remains a distant memory in our collective consciousness. In this case, it seemed like the complex world just coped and absorbed the negative effects. Humanity’s ability to adapt even to the worst situations seems remarkable, but simultaneously, historical events have cascading effects. So, I am torn between the two viewpoints.

Raul Espejo: Do you think the world is increasingly moving toward fragility? The more fragile the world, the fewer chances there are to have shared responses because fragility will simply separate things. How do you solve that?

Boyan Angelov: I do think my fear is, personally, the lack of understanding of the world. I'm a big fan of Carl Sagan, who had this book, “The Demon-Haunted World”. He predicted the rise of conspiracy theories and pseudoscience. And I think the big reason for the rise of conspiracy theories and things like this is the lack of understanding of the world because it seems the world seems very complex. I think people have this fear that nobody's at the wheel. And I think this is my concern, too. Because sometimes things look outside of control. We tend to think I don't know, do we have a world government? But if you look at current events, no single entity is that powerful. Even the United States, with its whole power, cannot decide everything. If you look politically, we don't have a singular entity, and things in the world seem very hard to understand right now. And we delegate much of the understanding to data- and algorithm-centric systems - there's often no human involved. So, I think, in that sense, the world is fragile, or at least not under complete human control anymore. There are a lot of runaway effects from things we have done historically.

Raul Espejo: Don't you think that some of the issues we have discussed before even answer some questions, and there is no direction for answering this problem of fragility?

Boyan Angelov: I do think so. I worry about explaining those topics and getting more people on board. Again, cybernetics and complexity are not common topics for regular people who vote. I think for the average voter, it's very hard to see the world that way. They see, I mean, you can imagine, see the news, vote, make decisions, and feel powerless about changing the system.

I wanted to ask you this because I know you're involved in this Reinventing Democracy project. I also wanted to hear your thoughts about how to help people feel they have control over the world. Again, my big fear is that the system seems a bit too big to look at globally, but maybe the answer is to look at it locally and focus on solving those problems on an intermediate scale.

Raul Espejo: Well, I see your thinking is in the right direction. You know, I don't see things getting totally out of control. The problem is that things can get out of control, as we have experienced recently in Ukraine, the Middle East, and so on. But the point is that the different parts that we are getting out of control may well happen to come together, and I repeat, in some coordinated fashion, but not in the fashion that establishes a shared meaning and purpose for everything. So, fragility is something that may be very dangerous when you find that you cannot coordinate your actions with others. You recognize fragility, and that is significant. But when you recognize fragility, you discover that the parts can come together and be recognized as parts of a shared organizational structure. This organizational structure doesn't need to be one institution by any means. So that's when you say they all must unite into one institution. I think that's wrong. And that is likely to generate agility, separation, and all of the rest.

When do you recognize that all these elements can coordinate their actions and build up their support for making things happen according to the values and interests of the global organization? Then I think the problem is much, much more open to solution.

Boyan Angelov: I want to talk to you about the fragility. I call my project the “Study of Progress”. This movement started in the US under the name Progress Studies. So, it's a big history project that you look into how we can improve our progress as a species. There are different types of progress. We have economic progress, which most people mean when they talk about, but we also have social progress - for example, systems should be more democratic. And I think there's a lot of historical proof that more democratic systems tend to be more performant in economic terms, too. One theory I have is that I think about fragility, which is, I guess, good, much like a beneficial mutation making the global system more resilient. And there's system-ending fragility. This is the result of events that can, like in terms of progress, set us back a long time ago. To give an obvious example. My parents' generation was affected by the Cold War. A nuclear catastrophe would be such a system-ending situation.

What are your thoughts about progress in general? How much should we consider the fragility of our systems? How important is social progress as well, not just economic progress? Are we right to be afraid that our system will end? How do you see the progress of civilization?

Raul Espejo: Well, it's a very important issue, the one that you are talking about. Very important. And clearly, perhaps we should have given more emphasis to the economy in the past. And we are still putting too much emphasis on economic aspects. Economic aspects impose certain relationships with people and interests throughout the system. And that is where I think you may get the whole thing too inflexible, too rigid, because the economy, in a way, directs all the responses in one direction. “Let's get a better GDP”. “Let's get things more in the direction of producing more”. When, in fact, there are other aspects that we need to have in mind. These are: how much do we expect to have e people understand their values so that rather than being focused on the economy, we focus on values like respect, respect for each other, and the capacity to respond through interactions and not by imposing a particular direction because one of the things of the economy is that it directs us in one direction and that is let's produce more and let's get better outcomes in the sense of production. Well, it may well be that it is better to have respect for, you know, groups and respect for differences and increase the chances for people to come together.

-

The creator of the VSM, Stafford Beer, was a colleague of Espejo in project Cybersyn, and a key figure in management cybernetics. ↩

-

Here Espejo is talking about the variety in the sense described by Ashby in his "Law of Requisite Variety". ↩